Help Me Please

- Oct 30, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 1, 2023

part four of a blog series on compassionate self-witness and my new book still life

Stories as acts of telling are relationships.

Arthur Frank

This is wrong, all wrong. The neurological pain, bodily stress, nonlinear episodic confusion, the way I try to explain it and can’t—the people that name my experience according to their limited knowledge of science and sociological conditioning. The moralizing. The harsh judgements. The exhaustion from sleepless nights.

This is all wrong.

When my PTSD creates a whirlwind of confusion and I’m trying to fight my way out, others often respond with criticisms and/or the worst remedies for something they do not understand but aim to contextualize by their own lived standards and experiences. The compassion I need from them in that moment—a willingness to hear what is actually happening in my mind and body—is nonexistent. Their unmet needs carry them away to other relational sources while mine frequently go unmet completely.

For me, these are moments of intense grief. In her book It’s OK That You’re Not OK, Megan Devine says that “grief is love in all of its wild forms.” It’s difficult—all wrong—to love the people in your life and have them turn away due to ignorance and narrow interpretation.

I haven’t lost everyone in my life due to PTSD. Actually, over the past few years, I’ve gained a small army of new friends, readers, and followers. But key people who should have supported me at key moments in my process toward whatever sort of recovery I can muster, have left.

Today, this feels as much like a blessing as a curse. Losing dysfunctional community opens territory to gain a more functional one. My life is not all PTSD but knowing that there are individuals around me who will be there when it is, as much as when it’s not, is comforting.

PTSD induces grief—grief concerning both the past and present. As Devine fleshes out in her book, few people want to be around a grieving person. There is a push to get them to move on from life-altering circumstances. And there is often a moralization of the grieving person’s need to cry unceasingly, rage again, reel in the waves of loss rushing over them. One can’t predict how long it will take to grieve through a loss; and, in truth, some things are simply grieved forever.

My own grief has diminished in relation to some of my life experiences but seems to remain for others. Some people have stuck around through these griefs and others have left, often assaulting my grief more. Let’s face it, when confronted with pain, we are cowardly beings. Living with PTSD and its griefs has taught me to be more cognizant of my own cowardice and far more empathetic toward those, like me, who are reeling. Much conditioning and self-talk goes into disarming my impulse to judge or react to their grief from personal discomfort—as well as my own.

“Self-compassion” says Beverly Engle in It Wasn’t Your Fault, “is both a process and a practice. You don’t suddenly become self-compassionate.” In the moments my brain and bones ache from another episode of PTSD, I also want to divorce myself from myself. My own grief is personally uncomfortable. I am the coward condemning my body for reacting to old memories and not staying with me in the moment I needed to be present for something that is often incredibly important to my welfare or joy. In those moments, I have not always helped others show me compassion, but have instead anticipated their judgements; after years of learning that there are those who will judge me, it has become a possibility I expect.

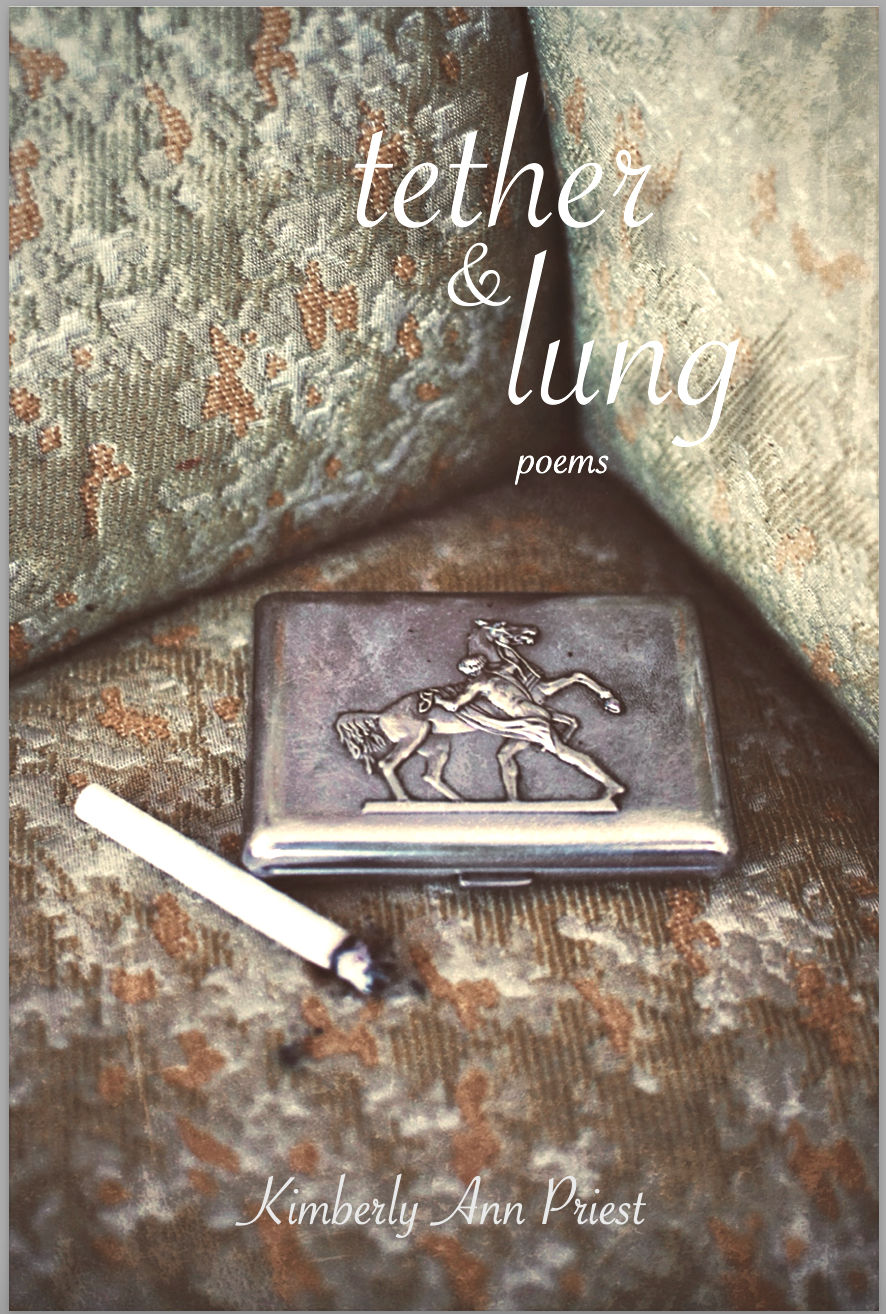

still life, my book, taunts my expectations. What do I expect from my readers, my audience? Will they judge me too?

I don’t know. It seems that the most self-compassionate thing I can do, I suppose, is love this book for myself. The cover is impressive: a black and white photo I took of a tiny abandoned home, white like the house I was molested in long ago. There is a large spot of yellow, like a sun, coddling the book’s title. And my name at the bottom is evidence that this is my art, my testimony, my life.

The danger of living is knowing that there are those who will mistreat us no matter what we do to ensure our own safety, no matter how much goodness we release into the world, no matter where we exist in the demographics and margins of society. The danger of producing this book is knowing that there are others, by my evaluation, who will mistreat it. Anything can be abused.

The joy of producing this book is knowing that there are hands that will hold this item I have crafted of sweat and tears and physiological pain and thank its poems for aiding their own process with similar pains and griefs.

This is all right. Putting the story out there. Lifting my eight-year-old body out of her fisted corner, warming her open and relaxed with extended embrace, letting her carry the water of her anger and shame in her body and letting it river and stream, walking with her from room to room until she is ready to open the front door of her little world and venture to the front yard of a larger world as the natural elements touch her harmed body—staying with her with each flinch and impulse to flee her own senses. Here she is, a still life inside this little book; here I am turning the door open.

Help me please.

This is the fourth and final of a series of blogs I will write on assault, trauma, and compassionate self-witness, as well as the hope that comes from taking the time to sit with ourselves in the dark. After all, as Martin Luther King once said so brilliantly, “But I know, somehow, that only when it is dark enough can you see the stars.” In our darkness, the hope of gentle light.

Order still life from PANK Press in October of 2020 HERE.

Comments